(Click here for Part 1)

In the weeks after 9/11, I stopped writing fiction. I carried my 35mm camera everywhere and photographed the beautiful. I didn’t turn my lens on the smoldering pit or the jumbles of dusty teddy bears and memorial gifts. These were documented plenty by the professionals, who were there in droves, paying attention to the rescue and recovery workers, the remnants of the towers, the smoke. What I noticed was the changed light, the newly empty sky over lower Manhattan. The sun was no longer blocked by the towers.

When we moved back into my office building, after the all-clear, management had brought in a few perks to boost morale. One of them was free Starbucks coffee, the better to keep us toiling late on the rescue of our data and deals. One was free popcorn, the better to keep our stomachs aching, like sandpaper moving through the old GI tract. And one was the installation of temporary walls over the windows that looked out at the place where the towers used to be. To make the temporary walls festive, and to help us to access our innocence again, they hung funhouse mirrors, so we could look at many versions of ourselves while we enjoyed our free coffee and popcorn.

Funhouse mirrors. Not making this up.

That was one of the absurd, beautiful things I photographed. I printed and framed one: a self-portrait, multiversioned and blurred and distorted, the way we all felt downtown in the winter of 2001. I’ve searched for the right words for this feeling ever since.

In retrospect, I’m glad I kept the camera handy instead of the pen. What I needed to do was look out, not down. I needed to see what was happening. There would be plenty of time to write it down.

✥

This isn’t really turning into an essay about craft. At least not the craft of writing. Perhaps it’s about the craft of being. Everywhere, suddenly, were posters: If you see something, say something. It seemed too knee-jerk to me. It was too early to speak. Our Yemeni bodega man risked arrest just by existing. Brown people were everywhere subject to furtive words and whispers by the terrified non-brown, who seemed not to understand that there are all kinds of terror, and that terrorists are angry for a reason, and God forbid I should say something pro-Muslim to someone who lost someone the other day. So I said nothing. I wrote little. But I looked. I looked a lot. I went out on my lunch hour with my camera and looked. Everything went into the image bank, and leaked out years later, in dreams. And later, on the page.

And yet I’m grateful for the two things I wrote during the aftermath, letters reporting to friends and family that I was bearing up. The friends were curious, and frightened, and too far away to pitch in. So I reported. Here is the second of the two letters, full of raw language and sleep deprivation.

10/2/2001

Dear family and friends,

Again, I apologize for using the bulk email approach to keep you apprised of developments here. I have been very bad about returning calls and I promise when I am not so sleep deprived I will be more diligent and considerate.

At long last, I now have a temporary office space until I get to go back into the World Financial Center (WFC). I am now sitting in a cubicle at the corner of Broadway and Fulton, right across from St. Paul's Chapel. My new cube is on the 4th floor of 222 Broadway, and I have a window that faces the former World Trade Center (WTC). Ironically, my new location is actually closer to the disaster site than my old one. But since this building is not physically connected to the WTC and miraculously sustained no damage from the flying rubble, it is pretty much ok to use.

Basically I have been getting here at 8 AM every day (unfortunately weekend too) and leaving late at night, so I have had the opportunity to watch the continuous scenario outside. The back of St. Paul's faces the remains of the WTC, and the front faces my "new" office building, which is actually at least 40 years old. My building is on the edge of the militarized zone which is restricted to law enforcement, rescue/recovery workers and those who support them on an "official" basis, and professionals hired to clean up the mess and assess the damage. Boy, is it a zoo. Even restricting the area to "official" people, there are plenty of them to go around. St. Paul's is inside the militarized zone, operating as a food/sleep/prayer station for the workers, complete with a row of portable toilets lining the street in front of the church's facade. Despite the toilets, I find the church an interesting and inspiring thing to look at day in and day out while we try to resurrect our database. We can gauge the time of day by watching them lay out the buffets on the front steps. I learned today St. Paul’s is Manhattan's oldest public building of continuous use. Despite the horrible things that went on directly adjacent to it, the church has survived well and continues its service, even as many of the newer buildings around it have become either bombed-out shells or piles of rubble. And, I might add, most of the beautiful old gravestones are still standing. When the flowers grow back, I imagine the church grounds will look much like they have for two hundred years.

My building appears to be in a semi-militarized zone, which means sometimes I have to show my badge to walk down the street and sometimes I don't, depending on what vehicles need the street. Saturday morning they made me circle several blocks to get to the entrance. When I finally reached the checkpoint, some workers from Krispy Kreme were bringing in donuts, I presume to one of the food tents. One of the NYPD said maybe he should "inspect" the contents of the boxes. Cops, donuts, it's nice to know that some things don't change. People are genuinely trying to keep their sense of humor in a confusing and painful environment. Of course I had to tease the cop about being a donut specialist. The feeling in lower Manhattan right now is one of genuine friendliness, along with the shock that comes from seeing the emptiness where the towers once were.

We are sharing our cafeteria with cops, National Guard, and firemen from all over the country, who can come inside for a free hot meal and a nap. The cafeteria is on the fifteenth floor, which offers a very clear aerial view of the WTC ruins. In general, the cops sit near the windows and look in awe at the slow progress. The firemen sit away from the window, clearly having already seen enough. They are dressed in construction gear which I presume has been donated, and they leave dust footprints on the carpet. The first day I went in, there were tons of firemen eating up there, but as the week wore on, their numbers dwindled. My first theory was that they were all gourmets and found better food elsewhere. My second theory is that they were not comfortable getting on the elevator with fussy bankers in clean, expensive suits, loaded down with laptops, palm pilots, and cell phones, talking about money. To tell you the truth, I have never been entirely comfortable with that “suit” element, but over time I have grown to have compassion for the wealthy too. But if I were a fireman on a job such as this, I might not want to eat lunch with the likes of us.

Outside, there are a lot of gawkers. National Guard are fairly polite as they ask people to refrain from photography. At first I thought it was gross to come down here just to look, but then, as I watched people's faces, I realized people *need* to see it. It's not about saying "I was there." It's about proving to yourself that it really happened, that it wasn't just a bad dream. I have found that sitting and watching the workers and the smoke rising from the pit has helped me to come to terms with the reality and the magnitude of what has happened to our city. It has also helped me not to feel sorry for myself for working sixteen hour shifts. At least I have a comfortable chair and a toilet that flushes.

Which leads to an interesting point...I am awed by the infrastructure that has materialized here practically overnight. They have built a large tent city, complete with a portable McDonalds parked in front of the shell of WTC 5. This would never be possible in, say, a third world country. This kind of devastation is unfamiliar to most of us in North America and people are beside themselves trying to pitch in. While I imagine the instinct to help is pretty universal, the fact that we have the resources to do it is particularly American. The surplus of donated supplies is a testament to that.

However, I would not exactly call this tent city a well-oiled machine. It is too big for that to be possible. People are really cooperating, but there are so many government and private organizations involved that the information flow is problematic. This became very clear to me on Friday, when my colleague Marina and I went into the crime scene to retrieve some computers.

I'll start from the beginning because the story is actually pretty funny. We got a call at about noon that we got clearance for two volunteers to go into the building. We had already sent in one commando group consisting of my boss Anne and two others from my team. They got our servers out, which has saved us loads of time because we don't have to restore as much. (Apparently, restoring a forty gigabyte database is not trivial, even if you have it all backed up on tape.) However, we also wanted to bring out two high-power CPU's with proprietary code on them. We have all been given laptops but they do not have the juice to do all our calculations in a timely manner.

(Again, I realize our computer problems are trivial in the grand scheme of things...like Mike Piazza said the other night, "It's just baseball, it's not life or death." We're all just doing our jobs, while we still have them.)

Since Marina and I had not been in the WFC yet, we both volunteered. I was actually keen to go in and see the state of our facility, since I had heard everything from “the building is falling” to “we’ll be back in next week.” While the tech support guys worked on getting us individual clearance to go in, I went outside and bought a backpack, a luggage cart, two flashlights, some veggie sticks, and two little bottles of red wine. I figured if we got stuck in there (which we were warned was likely), or if the building fell on us, we could at least have a toast. Then I charged my phone and worked on our database until we got further instruction.

At 4:30, Marina and I proceeded by subway to our first stop, Merrill Lynch’s technology bunker (huge), which is in an unmarked warehouse in the meatpacking district. There we got notarized passes and a second luggage cart. We took the city bus uptown to W. 38th Street to catch a 6:45 “special” ferry to the WFC. We were the only passengers on the ferry—we felt special indeed! It dropped us off in front of the WFC’s Mercantile Exchange and we tried to figure out where to go next given all the roadblocks between us and our building, which is a half a block from the water. A National Guardsman told us to walk up to Warren St. So we did, essentially walking the same path I did on September 11. We could not help looking back at the emptiness where the towers once were, remembering that day. Cops directed us to a checkpoint near Stuyvesant High, where we asked how to get the escort we required to go into the building. NYPD sent us to National Guard, who sent us to NYPD. We went into a tent where they had a faxed list of who was supposed to be allowed in. We were turned away, told to go ask some cops, who were the same cops who had directed us to the tent. Several National Guardsmen had words with each other over what the policy was supposed to be. The answer was repeatedly “I don’t know. Go ask those guys over there.” Several people said, “Oh, you’re from Merrill? Then what you need to do is go to Fulton and Broadway. There you can get clearance to go in.” Fulton and Broadway? That’s where we started! The whole time we were laughing that maybe if we were younger and cuter it would be easier finding an escort.

Then we walked basically back the way we came, alone, greeting the same law enforcement guys who recognized us and let us pass. We saw a street cleared for vehicles and decided to walk down it and see if anyone stopped us. We just acted like we knew what we were doing and eventually got to the building. The air definitely smelled like death. I realized that we were probably very close to the morgue tent. It was one of those smells that is familiar and human and it surprisingly did not bother me as much as the smoke and chemical dust in our new office. Death is a very sad smell but not a scary one, at least to me. It only reminded me that these people are no longer frightened and suffering.

We tried several entrances to our building and finally gained admittance. As we entered the building at about 7:30, Marina remarked, “It has taken us three hours to go four blocks!”

Inside they checked our credentials and assigned us to Steven, a Merrill security guy who would escort us to our floors. We took the freight elevator to the 21st and went into the server room with flashlights to get the first machine. It took us awhile to find it in the dark. Then we took the elevator to the 20th floor. The emergency lights were the only power on. I went to the bathroom with a flashlight, which was surreal, given how many times I have gone to that bathroom. Our floor was pretty much how we left it. We had a checklist of smaller items to retrieve and went through it. While we did this, Steven went around the floor to water all the plants. For some reason this almost made me want to cry. While it seems like a trivial gesture, he seemed to take pleasure in keeping them alive while we were away. I gave him my spritzer bottle and told him he could keep it if he wanted. We packed the machines in boxes on our two luggage carts. Around them we put family photos and documents for our colleagues. I changed into my good sneakers, which were still under my desk. We went to a corner conference room to take one last look back at The Pit. It was lit with floodlights as the workers continued their jobs. Smoke was still rising from the remains of the towers. The emptiness was palpable. Dead palm trees lay in pieces in the WFC plaza.

We took the freight to the lobby, where we unpacked our boxes so they could check the serial numbers on the equipment. The next Merrill ferry was scheduled for 10 PM. (My boss was not so lucky on the previous excursion—they had to stay in the building for 12 hours.) We were hot from all the exercise and asked to wait on the dock. Steven escorted us out via several strange basement passageways and the WFC plaza. As we left he told us of his experience on the 11th. He was doing his job, helping people to get out of the Winter Garden (the big glass atrium) when the North Tower collapsed. An older man was having trouble running when the atrium’s glass started to fall. A big piece landed on him and sliced his body in half. Steven seemed haunted by this image. We gave him what encouragement we could and thanked him profusely. On the dock, we opened our bottles of wine to celebrate being alive.

To our surprise, a ferry stopped at 9 PM to pick us up. They were on their way to Jersey City, and had noticed us on the dock. We rode to Jersey, then up to 38th St. again, remarking on how surprisingly easy the expedition had been. We ordered a car to pick us up at the ferry terminal, then went back to the bunker to pick up our coats. The car dropped us off at Spring and 6th, where a shuttle drove us through the checkpoints down to Chambers. Then we wheeled the carts six or so blocks more to 222 Broadway with the computers, arriving at about 10 PM.

When we went into our new “command center” (a converted conference room), our head programmer Inna burst out laughing as we unpacked the boxes. Turns out one of the machines we retrieved was the wrong one. We should have spent more time in the server room with the flashlights. I was mortified. We all burst into giggles, including our boss Anne, who happened to call on my cell phone as we made the discovery. Marina, whose cup is usually half full, said, “Think of it this way. We got one good machine out of the building.” Thank God for Marina. I had a coffee and sat back down to continue working on the data.

I should tell a little about the mood at the office. People are exhausted and stressed, especially management, HR people, and tech support. Everybody looks thin. There is concern about the air quality in the “new” building. Many of us are having sinus problems and have lost our taste buds. We think about all the pulverized things we are breathing: asbestos, concrete, drywall, heavy metal, carpets, computers, plastics, human beings. People burst out crying occasionally in their cubicles. Merrill has had to change its bereavement policy. In the past, we were allowed a week for loss of immediate family, and used personal days for other loved ones. Now, with so many memorials to attend, they are allowing paid half days for loss of friends.

I am happy to say that I have lost no one close to me. I was especially worried about one client at Oppenheimer Funds (South Tower WTC), with whom I have a friendly phone relationship. He emailed me the other day asking for data. I figured if he is ready for data, then we really have to get our act together. I was very relieved to hear from him.

Over the weekend, we have been a small group, me and my three Russian colleagues. We found a place around the corner, Blini Hut, where they can order in Russian over the phone. Our “command center” is now a pantry with Russian pastries and laughter. Last night Marina came to me with a long question. Unfortunately she asked it in Russian and didn’t realize it! Tanya, sitting next to me, about laughed until she peed her pants.

We had a meeting in Princeton about a week ago for the entire New York research division. Everybody was hugging each other, dispensing with business propriety, glad to see each other again for the first time. Andy, our big boss, had trouble speaking to us through his tears. It must have been a tremendous relief to him to see all 300+ of his New York employees in the same room. He recounted his experience of the 11th, and could barely talk about seeing all the emergency vehicles driving into the scene as we walked away. We now can imagine what happened to many of these people. I remembered the last time I attended a big research lunch like this—it was about two years ago in Windows on the World. I remember looking down at the World Financial Center and thinking how small our buildings looked. Now, they dominate the skyline.

In general, I am feeling better. Tired, but less numb. Last week I was flipping channels and stumbled across the New York Philharmonic doing the Brahms Requiem. It was a huge, earnest, and skilled choir, and the soloists sang the work from memory. It struck me that these were people grieving for their own city. I remembered how much Mom used to love the Requiem, and how we listened to it after she died. I found myself glad for her that she did not live to see this happen. I missed her, and all the dead people I loved. And as the Requiem finished, without applause, I just sat and sobbed.

Hug each other and stay well.

Love,

Anne

What would a real writer have done with these letters? Would she have turned them into a real essay to submit for real publication in the days following the attacks, when the reading appetite was still there, when people were still hungry for information? If I were a real writer, would I have taken my experience as impetus to report it to the world, to do my part that way, instead of the way I did, which was to double down on my finance career and stick it to the terrorists through database retrieval?

Was I a writer at all? Why did I quit fiction and take up photography that fall?

On that surreal day, on my long walk away from what was left of the towers, I had some time to think, and the one thought that kept coming back was what am I doing here? These are not my people. I am an artist. I resolved to plot my exit from the financial industry; there was surely some other way to make enough money in New York City. I needed to be with my people. The rich were under attack. Why was I hanging out with them?

But then a few days went by and I had not seen my colleagues. We had been separated in the chaos on the street, and we were worried. When we finally saw each other again, we hugged like family. What I hadn’t known, walking away from the horror, was that these people would become the only people who actually understood what I had experienced. We were bonded through the shorthand—the knowing nods, the permission to laugh at it. We were alive and we felt alive. We were jumpy when planes flew over, when sirens went by. Other people, if they felt like it, could talk about other things. We talked about only this. Maybe these were my people after all. Maybe a writer is never what I was.

✥

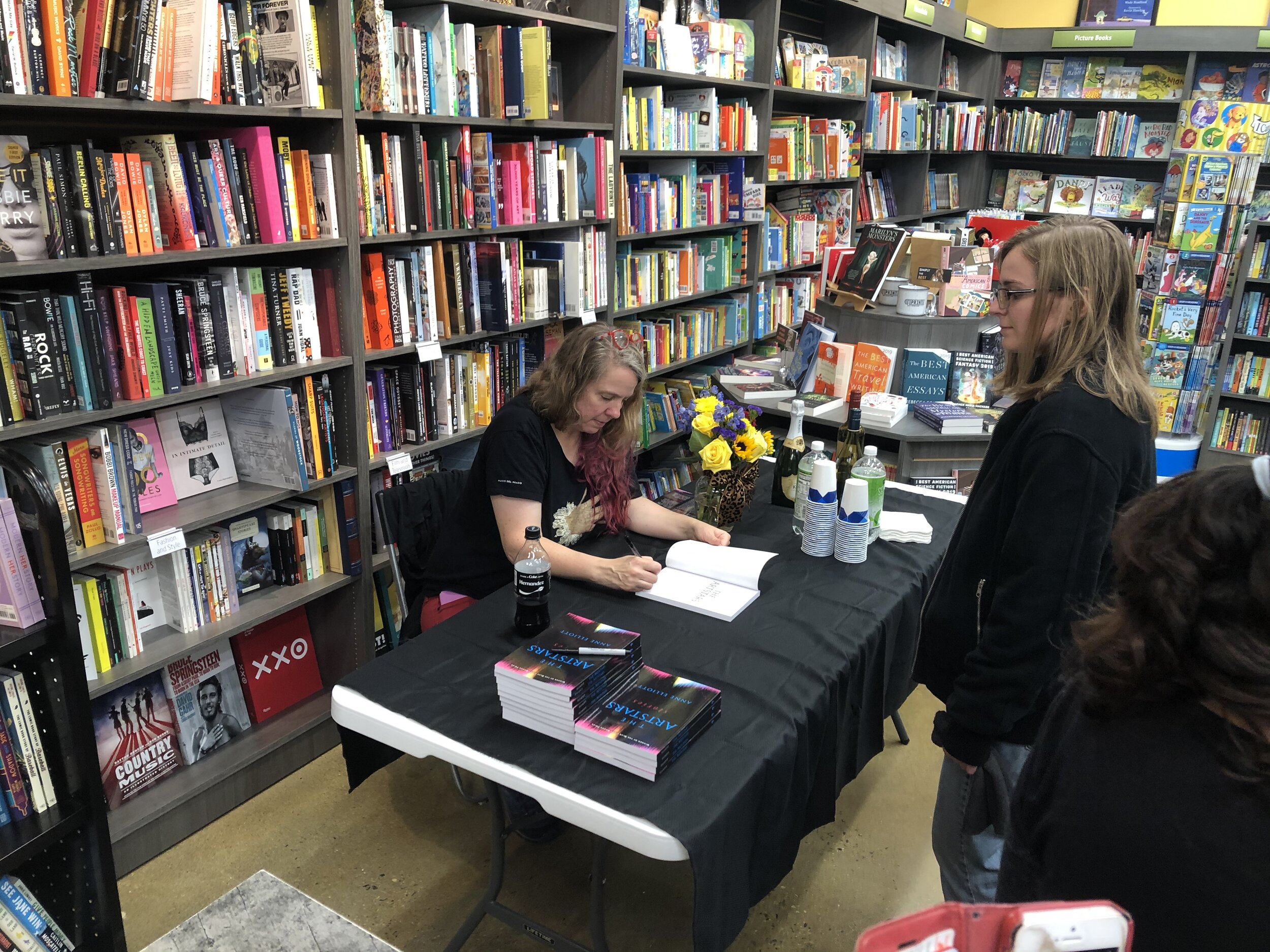

Time brings us back to who we really are, if we live long enough. I returned to writing. I put aside the camera. I lost most of the pictures, which were film, not digital. But the hard looking helped. That imagery is lodged in the compost of memory, and leeches into my fiction, including three of the stories in The Artstars. Two take place in the days and months after the attacks, and borrow liberally from my own experience at ground zero and at Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, where I sat in a room alone and thought about New York City and didn’t write a whole lot. And one takes place in the innocence of 1999, with scenes of corporate art in a fictional Merrill Lynch, and a long nod to the top of the Twin Towers, a place where I have positive memories.

I don’t worry too much about my right to write about it, not these days. I worry more about how to do it. The 9/11 attacks are so iconic they easily become cliché, especially for people who have no firsthand memory of them. This was my biggest fear, as I did my best to defamiliarize the imagery, to let my characters react in unpredictable ways, to pull back from the maudlin or cloying without disrespecting the traumatized and grieving. It has been one of my biggest tonal challenges to date.

✥

Here are some blog posts I wrote in 2005 while I was first drafting these stories. I forgot how hard I was thinking about this. In these essays I considered my narrative responsibility and craft concerns as well, particularly defamiliarization as a technique for bringing tired narrative alive, and consideration of 9/11 as an element of setting.

Does 9/11 Belong in Fiction? Part 1

Does 9/11 Belong in Fiction? Part 2

Does “It” Belong in Fiction? Part 3: Terror as Metaphor

(Click here for Part 3)